Rockwell Kent was born in Tarrytown, New York, the same year as fellow American artists George Bellows and Edward Hopper. Kent lived much of his early life in and around New York City where he attended the Horace Mann School. In his mid-40s he moved to an Adirondack farmstead that he called Asgaard where he lived and painted until his death. Kent studied with several influential painters and theorists of his day. He studied composition and design with Arthur Wesley Dow at the Art Students League in the fall of 1900, and he studied painting with William Merritt Chase each of the three summers between 1900 and 1902 after which he entered, in the fall of 1902 Robert Henri’s class at the New York School of Art, which Chase had founded. During the summer of 1903 in Dublin, New Hampshire, Kent was apprenticed to painter and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer. An undergraduate background in architecture at Columbia University prepared Kent for occasional work in the 1900s and 1910s as an architectural renderer and carpenter. At the Art Students League he would meet and befriend the artists Wilhelmina Weber Furlong and Thomas Furlong.

Kent’s early paintings of Mount Monadnock and New Hampshire were first shown at the Society of American Artists in New York in 1904, when Dublin Pond was purchased by Smith College. In 1905 Kent ventured to Monhegan Island, Maine, and found its rugged and primordial beauty a source of inspiration for the next five years. His first series of paintings of Monhegan were shown to wide critical acclaim in 1907 at Clausen Galleries in New York. These works form the foundation of his lasting reputation as an early American modernist, and can be seen in museums across the country, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Seattle Art Museum, New Britain Museum of American Art, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Among those critics lauding Kent was James Huneker of the Sun who praised Kent’s athletic brushwork and daring color dissonances. (It was Huneker who deemed the paintings of The-eight as “decidedly reactionary”). In 1910, Kent helped organize the Exhibition of Independent Artists.

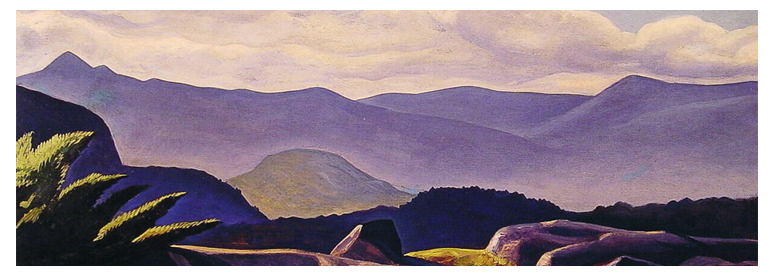

A transcendentalist and mystic in the tradition of Thoreau and Emerson, whose works he read, Kent found inspiration in the austerity and stark beauty of wilderness. After Monhegan, he lived for extended periods of time in Winona, Minnesota (1912–1913), Newfoundland (1914–15), Alaska (1918–19), Vermont (1919–1925), Tierra del Fuego (1922–23), Ireland (1926), and Greenland (1929; 1931–32; 1934–35). His series of land and seascapes from these often forbidding locales convey the Symbolist spirit evoking the mysteries and cosmic wonders of the natural world. “I don’t want petty self-expression”, Kent wrote, “I want the elemental, infinite thing; I want to paint the rhythm of eternity.”

In the late summer of 1918, Kent and his nine-year-old son ventured to the American frontier of Alaska. Wilderness (1920), the first of Kent’s several adventure memoirs, is an edited and illustrated compilation of his letters home. The New Statesman (London) described Wilderness as “easily the most remarkable book to come out of America since Leaves of Grass was published.” Upon the artist’s return to New York in March 1919, publishing scion George Palmer Putnam and others, including Juliana Force—assistant to Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney—implemented their avant-garde notion of incorporating the artist as “Rockwell Kent, Inc.” to support him in his new Vermont homestead while he completed his paintings from Alaska for exhibition in 1920 at Knoedler Galleries in New York. Kent’s small oil-on-wood-panel sketches from Alaska—uniformly horizontal studies of light and color—were exhibited at Knoedler’s as “Impressions.” Their artistic lineage to the small and spare oil sketches of James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), which are often entitled “Arrangements,” underscores Kent’s admiration of Whistler’s genius.

Approached in 1926 by publisher R. R. Donnelley to produce an illustrated edition of Richard Henry Dana, Jr.’s Two Years Before the Mast, Kent suggested Moby-Dick instead. Published in 1930 by the Lakeside Press of Chicago, the three-volume limited edition (1000 copies) filled with Kent’s haunting black-and-white pen/brush and ink drawings sold out immediately; Random House produced a trade edition which was also immensely popular. A previously obscure book, Moby Dick had been rediscovered by critics in the early 1920s. The success of the Rockwell Kent illustrated edition was a factor in its becoming recognized as the classic it is today.

Less well known are Kent’s talents as a jazz age humorist. As the gifted pen-and-ink draftsman “Hogarth, Jr.”, Kent created a wealth of whimsical and irreverent drawings published by Vanity Fair, New York Tribune, Harper’s Weekly, and the original Life. He brought his Hogarth, Jr., style to a series of richly colored reverse paintings on glass which he completed in 1918 and exhibited at Wanamaker’s Department Store. (Two of these glass paintings are in the collection of the Columbus Museum of Art, part of the bequest of modernist collector Ferdinand Howald.) Further decorative work ensued intermittently: in 1939, Vernon Kilns reproduced three series of designs drawn by Kent (Moby Dick, Salamina, Our America) on its sets of contemporary china dinnerware. Among his many contributions between the world wars to the world of publishing, for both an elite and a popular audience, are his pen, brush, and ink drawings that were reproduced on the covers of the upmarket pulp magazine Adventure in 1927.

Raymond Moore, founder and impresario of the Cape Playhouse and Cinema in Dennis, Massachusetts, contracted with Rockwell Kent for the design of murals for the cinema, but the work of transferring and painting the designs on the 6,400-square-foot (590 m2) span was done by Kent’s collaborator Jo Mielziner (1901–1976) and a crew of stage set painters from New York City. Ostensibly staying away from the state of Massachusetts to protest the Sacco and Vanzetti executions of 1927, Kent did in fact venture to Dennis in June 1930 to spend three days on the scaffolding, making suggestions and corrections. The signatures of both Kent and Mielziner appear on opposite walls of the cinema.

As World War II approached, Kent shifted his priorities, becoming increasingly active in progressive politics. In 1937, the Section of Painting and Sculpture of the U.S. Treasury commissioned Kent, along with nine other artists, to paint two murals in the New Post Office building at the Federal Triangle in Washington, DC; the two murals are named “Mail Service in the Arctic” and “Mail Service in the Tropics.” Kent included (in Inuit dialect and in tiny letters) a polemical statement in the painting, which caused some consternation.[4] In 1939, he joined the Harlem Lodge of the International Workers Order (IWO), an organization devoted to the social and economic welfare of the working public.

Kent’s patriotism never waned in spite of his often critical views of American foreign policy. He remained America’s premier draftsman of the sea, and during World War II he produced a series of pen/brush and ink maritime drawings for American Export Lines and began another series of pen/brush and ink drawings for Rahr Malting Company which he completed in 1946. The drawings were reproduced in To Thee!, a book Kent also wrote and designed celebrating American freedom and democracy and the important role immigrants play in constructing American national identity. In 1948 Kent was elected to the National Academy of Design as an Associate member and in 1966 he became a full Academician.

In the 1950s Kent became increasingly supportive of Soviet-American friendship, peace, and a world devoid of nuclear weapons. Along with hundreds of other prominent intellectuals and creative artists in America, he became a target of those in league with Joseph McCarthy. The rise of abstract expressionism cast a further shadow over his art and representational painting in general. Kent’s passport was revoked by the U.S. State Department in 1955 and he filed suit to regain his foreign-travel rights. In June 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court in Kent v. Dulles affirmed his right to travel by declaring the ban a violation of his civil rights. After a well-received exhibition of his work in Moscow at the Pushkin Museum in 1957–58, Kent donated several hundred of his paintings and drawings to the Soviet peoples in 1960. He subsequently became an honorary member of the Soviet Academy of Fine Arts and in 1967 the recipient of the International Lenin Peace Prize. Kent specified that his prize money be given to the women and children of Vietnam, both North and South. (The nature of Kent’s gift is clarified by his wife Sally in the 2005 documentary Rockwell Kent, produced and written by Fred Lewis.)